This is the fourth in a series of blog entries leading up to the release of my new book, Chasing Shadows, written with shark biologist Greg Skomal. Click here to see all the blog entries in this series.

316 men came out and the sharks took the rest.

The last two entries in my ten-day countdown to the release of my new book CHASING SHADOWS, written with shark biologist Greg Skomal, focused on Jaws and the so-called “Jaws effect.” There is no doubt that the movie Jaws influenced Greg’s interest in the species, and as we point out in the book, the movie had a lasting effect on many individuals, but we want to be really clear that it was not just Benchley’s novel and the ensuing Spielberg film that shaped the public’s perception of the white shark. In the chapter titled “Going to Sea,” we talk a bit about World War II and the influence the war had on our collective perception of white sharks. Here’s an excerpt:

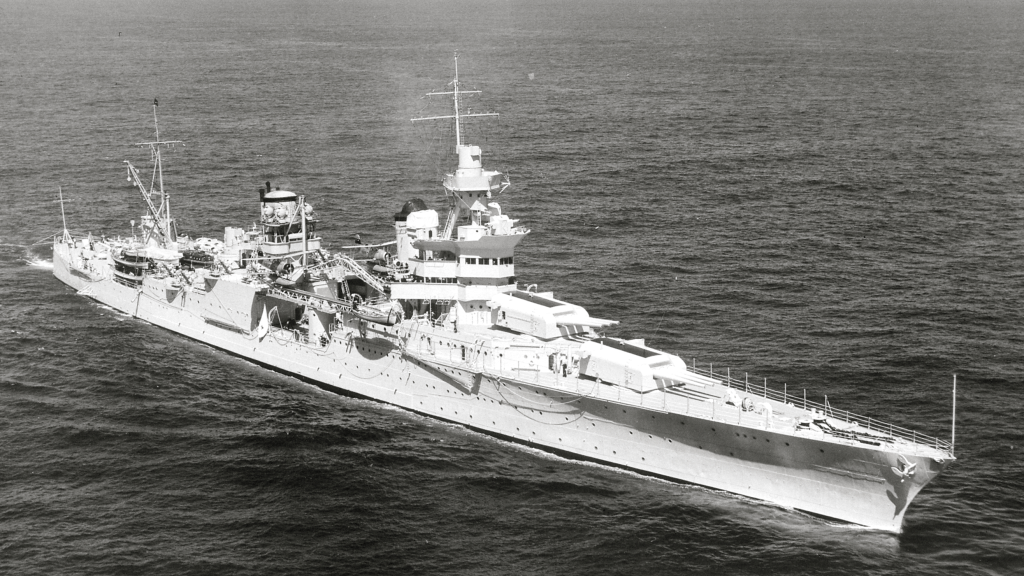

Jaws, and in turn the white shark, get much of the credit for creating the deeply rooted societal fear of sharks, but the reality is that the seeds for a ubiquitous shark-related psychosis are more firmly rooted in wartime, when shipwrecked sailors and downed airmen found themselves in what were commonly described in news reports as “shark-infested” waters. There was surely some gruesome irony to the fact that a young man would survive his ship being torpedoed or his plane being shot down only to face the threat of shark attack in the water. As atrocious as warfare was, the notion that there was something even more ghastly and primal lurking just beneath the surface was enough to traumatize a generation. Capitalizing on these deep-seated terrors, “shark-infested” waters became a speculative (at best) set piece of many newspaper stories, drumming up a crescendo of irrational fear of sharks. It wasn’t, however, all hyperbole. As Jaws pays homage during Quint’s penultimate scene, perhaps the worst disaster of World War II for US servicemen was the sinking of the USS Indianapolis, where many sailors were indeed killed and some eaten by sharks.

As we point out in the chapter “Unlikely Partnerships,” the wartime “shark-related psychosis,” was the major impetus for shark science, and that science was largely funded by the military:

[M]ost of the shark research in the middle of the twentieth century was firmly focused on how to keep people safe from shark attacks. Nearly all the pioneering shark researchers were associated with that work, and most—including Eugenie Clark, Albert Tester, Richard Backus, and Perry Gilbert—were present at a 1958 conference titled “Basic Research Approaches to the Development of Shark Repellents,” which was funded by the US Navy’s Office of Naval Research.

It wasn’t until Jack Casey’s interest was piqued after the 1960 unprovoked attack on John Brodeur and the subsequent scientific work in the New York Bight that shark science in the western North Atlantic took a dramatic turn.

But more on that tomorrow…

If we’ve piqued your interest, you can learn a whole lot more by reading our book Chasing Shadows, which will be out on July 11th.