One of the questions I asked Greg Skomal as we were writing Chasing Shadows, our new book that published earlier this month, was when did he feel he knew that sharks in shallow water off the Cape’s beaches were not just an anomaly. When did he know that this was the new normal? Turns out that it was 13 years ago today on 30 July 2010. Here’s an excerpt from the chapter titled “The New Hotspot”:

By the end of July 2010, there was no doubt that white sharks were indeed patrolling the shallow water off Cape beaches, especially from Chatham out to Monomoy. The first sighting was by George Breen, who was flying his plane over Nauset Beach on July 11 when he saw a fifteen-foot white shark hunting seals less than one hundred feet off the beach. The media labeled the shark as “aggressive.” Was this the confirmation for which people had been waiting? Was this proof that 2009 was not an anomaly? Captain Billy Chaprales thought so. “I’ve been a commercial fisher for over forty years,” he said, “and I only saw three until last year.”

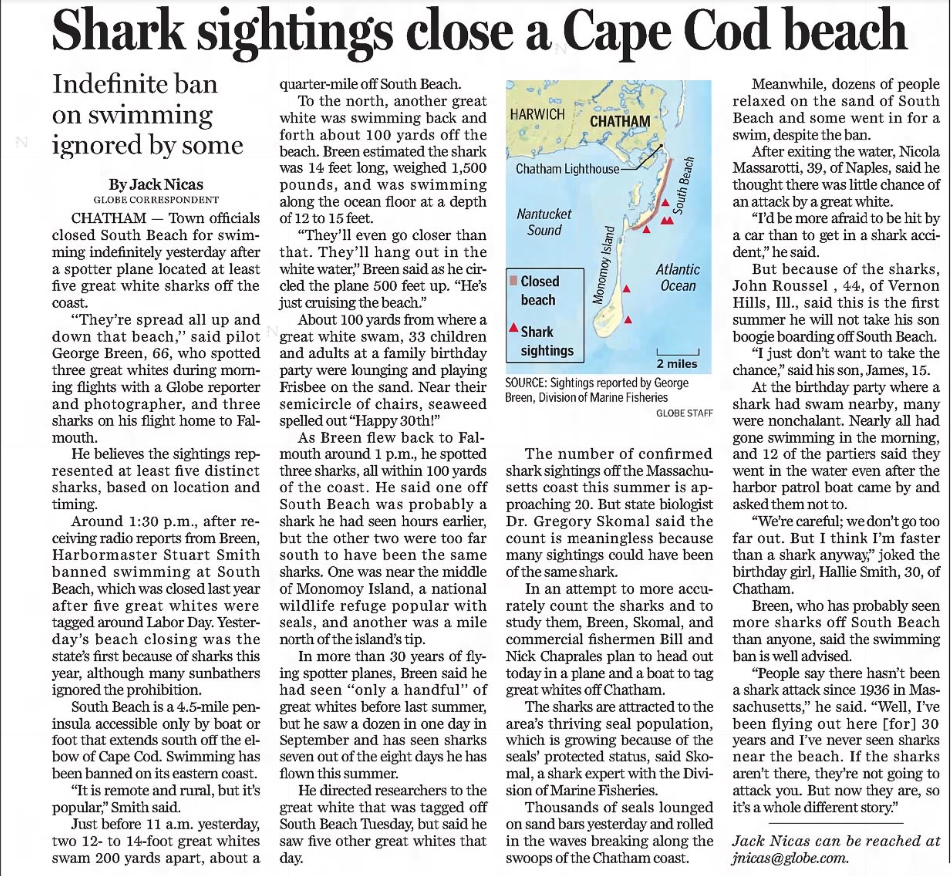

On July 30, George was again up in his plane, this time with a re- porter and a photographer who were covering the shark story. George spotted two sharks swimming parallel to South Beach a couple hundred yards apart. The larger of the two, George estimated, was fourteen feet; the smaller one was probably twelve feet. George continued along the coastline and spotted another fourteen-footer about one hundred yards off the beach. “They’ll even go closer than that,” he said over the inter- com to his passengers as he circled so they could get a good look. “They’ll hang out in the white water.” George leveled off and set a course to return to Falmouth, but before they left Monomoy’s beaches, he spotted three more sharks. One of them possibly was a shark he’d seen earlier, but he felt confident the other two were ones he had not observed earlier.

George radioed Chatham’s harbormaster to tell him what he’d seen, and the harbormaster, based on George’s report, made the decision to shut South Beach to swimming indefinitely. It was the first time that year that a beach had been shut to swimming. Harbor patrols made their way along the four-and-a-half-mile-long, unguarded South Beach and informed people of the swimming ban, but many people continued to enter the water anyway.

31 Jul 2010, Sat · Page B3

I’m not a sociologist, but it’s fascinating to me how people respond to swimming bans in the face of credible sightings near beaches. I’m certainly no alarmist, and I was glad it was not my job to tell people what they should and shouldn’t do—but what happened to common sense? If I was on South Beach with my family, and a patrol boat came by saying that a swimming ban was going into effect because of credible white shark sightings, I would certainly not swim. When George called me later, he told me that when they’d spotted the first sharks, they were not far from a large gathering on South Beach.

“Seaweed was arranged on the sand to spell out ‘Happy 30th,’” George said. “It was a birthday party. They were playing Frisbee and en- joying the day, oblivious to the large shark that swam less than a football field away.” Later, when the party was alerted to the fact that a swim- ming ban had gone into effect, many still chose to go in the water. “We’re careful,” said the birthday girl when questioned by a reporter later. “But I think I’m faster than a shark anyway.” It was a joke, but still.

“Listen,” said Katie McCully, a forty-four-year-old lifeguard at Nauset Beach, “we swim the length of our protected beach on a daily basis, and we feel safe.”

“We live in a fear-oriented society,” said a minister in his fifties, who was training for a triathlon and was undaunted by the shark sightings. “I try not to.”

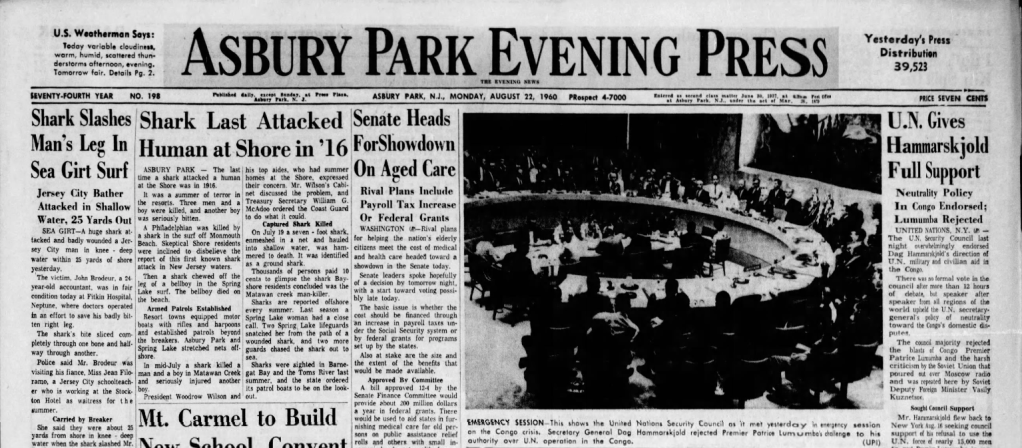

Like me, George didn’t get it, either. He’d been flying in the area for more than three decades, and he’d only seen a handful of white sharks from the air before the summer of 2009. This summer, he’d made eight flights and seen white sharks on seven of them. “People say there hasn’t been a shark attack since 1936 in Massachusetts,” he said. “Well, I’ve been flying out here thirty years, and I’ve never seen sharks near the beach. If the sharks aren’t there, they’re not going to attack you. But now they are, so it’s a whole different story.”

I wanted to keep an open mind because I didn’t have the data to show anything conclusive yet. Yes, there were more shark sightings. It could be an anomaly, but my gut told me that was not the case. I was increasingly convinced this was the new normal, which is why I was gearing up for more tagging. Gretel had been a big wake-up call, but there were many other indicators. When I dove into the data of credible white shark sightings between 2001 and 2009, there was a clear upward trend. Some countered, saying that the number of white sharks wasn’t increasing; instead, the effort put into looking for them was increasing. In other words, more sightings didn’t necessarily mean more sharks. But the data told me a different story. Much of the data were based on interactions with commercial fisheries, especially the bluefin tuna fishery and the groundfish fishery that targeted cod, haddock, and yellowtail flounder. From 2001 to 2009, as white shark sightings in the region increased, those fisheries were declining by as much as half due to regulatory changes. Those data suggest there was less effort and more sightings.

There was another possibility as well. The sharks might be exhibiting a dietary shift. Instead of feeding offshore in the Atlantic, the population was adapting to the growing number of seals and moving inshore to hunt. In other words, there were not more sharks; the sharks were simply concentrating in an area where people were seeing them more. This was an interesting hypothesis, and it made a lot of sense to me. After all, Frank Carey had theorized way back in 1979, when they’d observed those sharks foraging on the dead whale, that white sharks in the northwest Atlantic relied more on whale carcasses and offshore feeding than white sharks in other parts of the world where pinnipeds were in ample supply. When the pinnipeds return, as they’d done in the Farallon Islands, so too did the white sharks.

Whether there were categorically more white sharks or whether the white sharks were simply shifting their dietary habits from offshore feeding to inshore feeding was an interesting question, but each was not mutually exclusive. It was a question I wanted to pursue, but from a pub- lic safety standpoint, it didn’t really matter why there were more white sharks showing up in shallow water off Cape beaches. If they were there, they were there. And they were there—making me increasingly confident that I was looking at the next chapter in the white shark story rather than just glancing at a footnote.

Chasing Shadows is available now wherever you get your books, or come to one of our talks or signing events and we’d be happy to personalize your book. Here are my book-related events as of right now: